Memories of Iraqi Kurdistan

Michael Quentin Morton

Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC) surveys laid the foundation of

our geological knowledge of Kurdistan and, for this reason, are still highly

relevant to modern oil exploration. But these activities also involved IPC

personnel living and working among the indigenous people of the region, and

their memoirs of the time provide a fascinating insight into a forgotten aspect

of oil exploration.

IPC in Kurdistan

The Turkish Petroleum Company, the forerunner of IPC, mounted

an expedition to Iraq in 1925–6, which included a brief survey of

Kurdistan. Following the discovery well at Baba Gurgur in 1927, the

company’s focus was on developing the massive Kirkuk oil field. It was not

until 1946 that the region was opened up to oil exploration again.

As well as prospecting for oil, IPC was interested in the

Kurdish mountains because their geology provided important clues about

the structure of the region. But Iraqi Kurdistan had a troubled history as its

people sought autonomy from Baghdad, and there were periodic outbreaks of unrest

which made oil operations dangerous. Most of the area was accessible only on

horseback and, apart from railway rest houses at Kirkuk and Mosul, a consulate

house in Sulaimaniya and a few public works shacks elsewhere, company employees

had to rely either on the hospitality of government officials or – more likely –

travel with their own tents and assistants. Journeys usually involved a

courtesy visit to officials en route, a lengthy process since custom demanded

the killing of a chicken or a goat in a guest’s honour.

Many of the scientists employed by the IPC group of

companies worked in Kurdistan at some stage in their careers. Among the

notable geologists and paleontologists who came and went was the

enigmatic figure of Robert George Spencer ‘Doc’ Hudson. A man of craggy

features and exceptional academic ability, Hudson had been a professor of

geology at Leeds University before joining IPC in 1946. His task was to study

the fossils, mostly invertebrate, collected by the company’s field parties. He

brought with him years of experience of the fossils, stratigraphy and geology of

northern England.

Although reluctant to accept his first eight-month assignment to

Iraq, Hudson enjoyed it enough to spend a full year in the company’s

laboratories at Kirkuk. He stayed on with the company until 1958, writing

extensively on the geology of the region and leaving to the company a 12-volume

loose-leaf quarto ‘Guide to Index Fossils of the Middle East’. He was considered

a leading authority on the subject (and on the carboniferous geology of

northern England and Ireland) when he died accidentally from carbon monoxide

poisoning in his rooms at Dublin University in 1965.

Kurdish Chieftains

It is remarkable how Kurdistan won the hearts of the IPC people

who worked there. My father, geologist Mike Morton, often spoke of it as the

finest place he had ever visited on his extensive travels around the Middle

East. ‘It’s cold here now,’ he wrote. ‘I went up to the Persian frontier last

week. It rained here too – and snow fell on the mountain peaks around the camp.

It’s a lovely part of the East – high mountains, trees, streams, wild birds,

squirrels, and in the higher parts, wild pig, bears, and ibex. There are even a

few leopards.’

Apart from the beauty of its natural landscape, this was a land

of larger-than-life figures. Among its chiefs was Babekr Agha of the Pizhdar

tribe. He was tall, gaunt and with a patch over one eye and a large aquiline

nose. Dressed in baggy trousers, a brightly coloured cummerbund and wearing a

turban, he presented an imposing figure. The men sitting around his majilis had

all the charm and humor for which the Kurds are renowned.

In the 1950s, relations between the Kurds and the company were

good. On one occasion, Babekr Agha arrived at the IPC hospital in Kirkuk for a

medical operation. To the dismay of the British staff, a retinue of about 50

armed men, all of whom expected to sleep beside their chief, accompanied him.

Aftermuch negotiation, staff persuaded them to camp outside in the hospital

grounds. John Davies was the IPC surgeon, a man who was so devoted to his work

that he stopped people in the street and, if they looked interesting enough,

invited them to come for an operation. In the Agha’s case, the operation was

successful and the patient, on his departure, paid tribute to the IPC management

while his tribesmen jostled to get into the room.

Another prominent chief was Suleiman Agha of the Herki tribe. IPC

liaison officer, Ian Macpherson, would often visit him to pay his respects. At

one lunch thrown in his honor, Suleiman Agha provided the customary fare of lamb

and rice cooked in the Persian style with apricots and walnuts. Unlike the

Arabs, the Kurdish women were unveiled and moved freely around the gathering,

although they did not eat with the visitors. They wore bright colors that

clashed rather than matched but, as Macpherson observed, the effect could be

dazzling in the strong clear light of an Iraqi spring. At the end of the lunch,

the customary Kurdish gesture of approval – a series of energetic belches –

followed. To judge by their efforts, they were well pleased, but Macpherson kept

his counsel, prevented by company ‘regulations’ from making his own

contribution.

At the center of Kurdish life was the town of Sulaimaniya, then a

maze of narrow alleys and mud brick houses. For those houses built on a

hillside, the roof of one formed the courtyard of the next row above – and so

on. At the end of one of these alleys was the house where Macpherson stayed when

recuperating from illness. Kerim, the young Kurd who looked after him, fed him

well on kebabs and other local fare and, most memorable of all, breakfasts of

preserved apricots, mast (smoky yoghurt), cornflakes and wild honey. It was a

noisy house, surrounded by dogs, cats, small boys and donkeys. There was a small

mosque, and storks on nearby roofs snapped their beaks all day, making a

clattering sound that gave them the nickname ‘lag-lag’. On the veranda, in the

vine surrounding Macpherson’s bed, hundreds of sparrows with piercing voices

made sleep impossible after dawn.

The Kurdish tribesmen who assisted the survey parties were fierce yet intensely

loyal. My father was accompanied by Kurds as guides, chain men,

sample collectors and assistants. On one occasion, a tribesman appeared from

behind a rock, demanding, ‘Your money or your life!’ Omar, a Kurd in the

geological team and an ex-British army paratrooper, explained vehemently to the

highwayman that the geologists were his guests and eventually the man let them

pass safely. After they had passed by, Omar said, ‘That man has insulted my

nation, wait here, I am going back to kill him.’ He was eventually persuaded

otherwise.

A Case of Kidnapping

In July 1961 the Iraqi leader, General Abdul al-Karim Qasim,

ordered his troops to begin military maneuvers against the Kurds, an action that

precipitated a fullblown Kurdish revolt. Since most of the developed Iraqi

oilfields were in the north, a cry went up that the Kurdish troubles ‘smelt of

oil’. One Baghdad newspaper reported that the government had found rebel maps

printed with help from ‘imperialistic quarters’, and letters in English that the

Kurdish leader, Mullah Mustafa al-Barzani, had written to British subjects.

Mustafa had gone into hiding, the newspaper claimed.

In 1961, the rebels known as the Peshmerga raided an IPC exploration drilling

camp at Taq Taq. They left the expatriates unharmed but the company suspended

drilling operations and abandoned the well when Qasim confiscated the

non-producing areas. In October 1962, the Peshmerga raided Ain Zalah and took a

drilling superintendent prisoner. After a long walk to the Iranian border, they

released him.

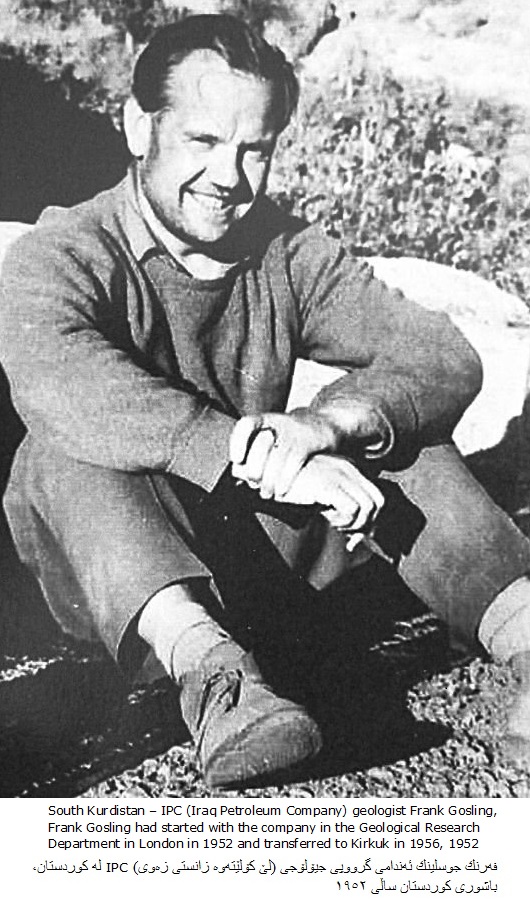

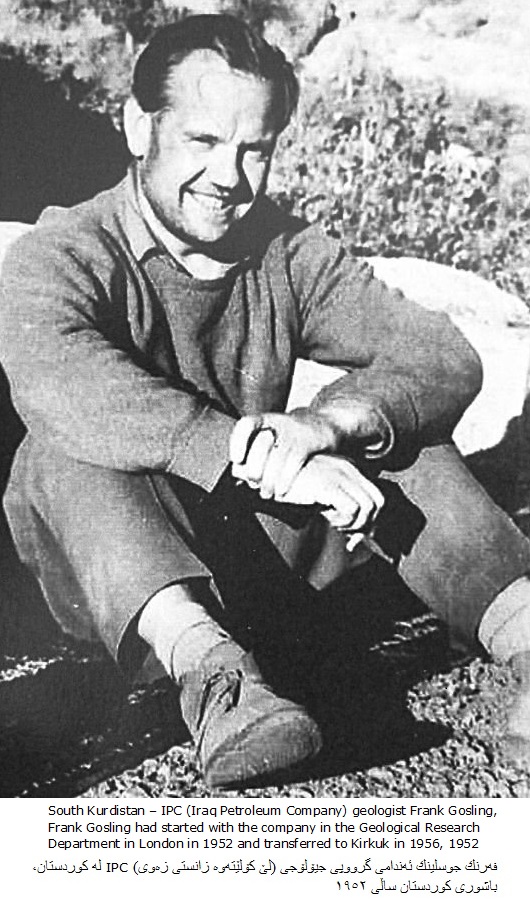

These troubles would have particular significance for one IPC

employee. Frank Gosling had started with the company in the Geological Research

Department in London in 1952 and transferred to Kirkuk in 1956. Here he worked

on exploration wells and field surveys mostly in the Kurdish mountains. One day

in November 1962, he phoned his wife, Pauline, to say that he was going to be

late for lunch. He was showing an Iraqi geologist, Adnan Samarrai, the geology

of an area some ten miles north-west of Kirkuk. Traveling in two Land Rovers,

the party of five arrived at a spot in the Qarah Chauq hills and the two

geologists began their inspection. Then four armed Kurdish tribesmen appeared.

Initially, the atmosphere was tense – one of their drivers was convinced that

the Kurds were going to kill them all. However, after some discussion, the Kurds

decided to release the men at sunset and slip away.

But then they changed their minds. Thus began a lengthy trek

through the mountains, arriving at the village of Bettwahta where they were

held for four long weeks. This was a large village tucked under a large

precipitous limestone cliff with caves at its base, providing the rebels with

shelter from overflying Iraqi MIGs. The leader of the Kurds, Barzani, eventually

arrived at the village to discuss Gosling’s release. He was described as a

‘fierce walnut-colored man of 59, with straight black eyebrows that almost met

across an eagle’s bill of a nose; a rough, obstinate old warrior’. After a long

discussion, Barzani agreed that Gosling could leave, but via Iran, since the

authorities in Kirkuk might accuse him of spying for the Kurds if he returned to

Iraq.

Winter had arrived – the weather was cold with rain and sleety

showers and icy water rushed down the mountain streams – and the next stage of

the journey was hard. Presently, after setbacks and sickness, Gosling

passed across the border into Iran, thence taken by train to Tehran. He arrived

back in London on January 9, 1963, almost three months after his capture.

Kurdistan Today

In 1972, the Iraqi government nationalized IPC’s assets,

effectively ending the concession. In 2013, however, a number of different oil

companies had 24 drilling rigs in Kurdistan and this year there will be 40, with

production expected to reach 250,000 bopd. A new pipeline to ship oil from

Kurdistan to Turkey has opened, although it is opposed by the federal government

in Baghdad, indicating that tensions between the regional and federal

governments have not been resolved.