The

Emergence of a Kurdish Rug Type

by William Eagleton

Oriental Rug Review, Vol. 9, No.

5

For most of us a rug type exists only after it

has reached international markets and has been seen and classified by collectors

and scholars. Until then rugs and other weavings can be present in considerable

numbers in their natural habitats without attracting the attention of the

outside world. This was the case with many Anatolian, Iranian, and Iraqi kilims,

bags, and trappings 20 years ago; however, it seemed unlikely that by 1988 any

major rug type was still awaiting discovery. Nevertheless, such a weaving has

recently emerged from the Kurdish heartland of Eastern Turkey.

|

|

This is not to say that these rugs were

never seen or recorded in print before. An

article by Anthony Landreau in The Textile

Museum Journal of December, 1973, provided a

black-and-white photograph of such a rug in the

hands of Kurdish villagers in the mountains of

the Turkish Hakkari region south of Lake Van.

Because the appearance of these large, heavy

Kurdish rugs in the market coincided with my own

research for a book on Kurdish weavings, I will

recount the story as it unfolded for me.

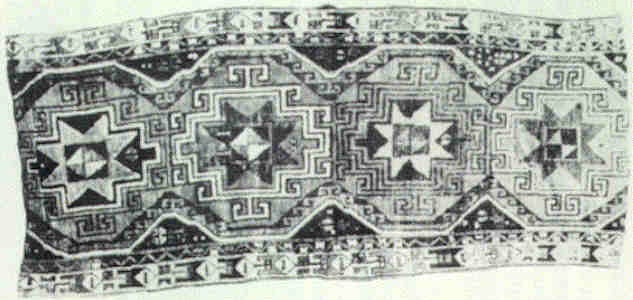

I first saw this Kurdish type in a badly

used-up condition in the suq in Mosul, Iraq, in

1981. It was blue, red, white and brown, and its

design was one of the two most common types,

available (Illustration 1). It was obviously not

related to the Kurdish rugs of northern Iraq,

and therefore I suspected that when the dealer

said it came from "the North" he meant Turkey.

I did not see another such rug until 1983,

even though during the period I covered the

major rug centers of central and eastern Turkey

looking for Kurdish weavings. Hence, it was

something of a shock when, in 1983, in an

obscure furniture shop in Mardin, there appeared

a pile of about 10 of these rugs in a variety of

designs, some in clear, bold colors, unlike

those of the neighboring Iraqi and Turkish Herki

and related tribal rugs. After the usual debate

on prices, I acquired four pieces, three of

which are illustrated in the Turkish section of

Kurdish Rugs. When I asked the vendor

where they came from, I did not take seriously

his familiar reply, "over near the

Russian-Caucasian border." Looking for something

more authoritative, I sent photographs to Burhan

Kartal, a friend and rug dealer in Van, even

though these rugs were not then available in the

several Van rug shops (there are now over 40).

Mr. Kartal replied that his investigation

indicated they were woven in the southern part

of the Hakkari mountains by the Goyan tribe, and

it is under this name that I classified them in

Kurdish Rugs.

|

Illustration 1. Hartushi common type

Later research has revealed that the rugs were

woven by all of the 11 sections of the large Hartushi tribe, of which the Goyan

were originally a part. Hence the preferred label for these is now Hartushi;

but, if you are looking for one in Istanbul or Konya, you will find that they

are usually referred to as "Herkis." This is a classic example of how a rug type

comes to be mislabeled by the trade. Turkish dealers have long known, and

carried in their inventories, rugs from the Van region labeled "Herki" after the

large nomadic Herki and associated tribes which, until recently, moved back and

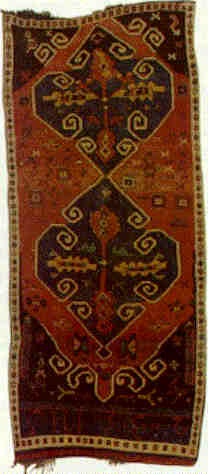

forth within the frontier area of Iraq, Iran, and Turkey. The Herki rugs,

however, are quite different in dyes, design, size and structure. The Herkis

(Illustration 2) are almost all in the roughly one meter by two meter format,

while the Hartushis are 125 to 160 centimeters wide and two-and-a-half to three

and-a-half meters long, with some even larger sizes available. By chance, two of

the rugs I found in the Mardin furniture shop were in a narrower runner format,

but this appears to be atypical.

|

|

Illustration 2. Hertki, c. 1940

Technical Analysis

Warp: Orange wool

Weft: Dark brown goat hair, two shoots

Knot: 5x7, 35 per square inch

Colors: BURGUNDY, blue, orange, brown, pink,

pink, white, yellow, plum

Size: 81"x41"

Edge: Sides: selvages overcast with pile wool,

color bands

Bottom: 4" kilim, four twinings

Top; round 9" plaits every 2" to v braids to 4"

kilim

|

As can be seen in the illustration, the Herki

rugs have rather complicated designs, either original or borrowed, and the

fields are usually adorned with a variety of small devices that are typical of

the tribal Kurdish repertoire. Most Hartushis, however, have small borders and

large dramatic medallion type centers repeated in twos, threes, fours, or fives,

or fractions thereof. The fields are relatively uncluttered.

Back to the process of discovery: it was not

until September, 1987, in a stopover in Istanbul that I saw two of these rugs in

a repair shop on the edge of the Istanbul bazaar. I asked a friend to try to

find others, but it was some months later that I discovered that, if I had

looked in the right places, I could have seen hundreds in Istanbul.

The next step was a visit a few months later

to Konya where Hakan Tazecan, knowing of my interest in Kurdish rugs, told me he

had just bought 35 Herkis. Would I like to see them? The prospect of seeing

Herkis after four years in Iraq where they were available in large numbers did

not excite me; but, when he displayed-his "Herkis," I realized he was in

possession of a hoard of what we now call Hartushis. Shortly thereafter, similar

hoards were found in Istanbul.

The mystery, however, had not yet been cleared

up. Why had these rugs not been seen in the market before, and why had they

suddenly appeared in such large numbers? All agreed that pickers were bringing

them in unwashed from the East by the truckload and peddling them in the

Istanbul and West Anatolian rug markets. Initially, the rugs were not as popular

with dealers as they might be with collectors since they are very heavy, require

considerable space, and are hard to manage, both by the boys who lay them out

and by the repair crews. Despite full, fleecy piles, many of them have holes or

other defects when they are collected from villages, and these must be corrected

before they are salable. Some of them are deemed non-commercial because of the

prominent use of bright orange or pink. In Turkey this can be remedied at little

expense by substituting more acceptable yarns.

We have not yet had an opportunity to submit

the fibers of these rugs for dye analyses. Many of the dyes, particularly in the

later examples, are probably chemical, including certainly the pinks and the

bright oranges. It is remarkable, however, that they rarely run with washing,

although in 'some rugs the reds of a certain period (perhaps 40 to 60 years ago)

have faded to abrashed light red. Many colors, however, remain vivid. The blues,

blue-greens, yellows, and browns, and most reds are impressive. The overall

effect is reminiscent of some of the crude, but much appreciated, Caucasian rugs

of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Most Hartushi rug designs are native to the

Kurdish Eastern Anatolian-Caucasian area, though an occasional piece is

influenced by other Turkish weaving. The execution, however, is from the mind,

or possibly from another rug, but not from a detailed drawing. Inquiries during

our investigation in the Van region in June, 1988, led to the conclusion that

the Hartushi rug designs, like the Hartushi (Van) kilim designs, are woven

interchangeably by all sections of the large Hartushi tribe. Hence, there is no

way to assign designs to specific sections of the tribe. The major rug designs

bear little resemblance to the repeat designs found in the Hartushi kilims. We

have found this to be the rule with other Kurdish tribal weavings as well. The

only exceptions are some of the simple borders where there may be similarities

between the kilims and the rugs.

|

|

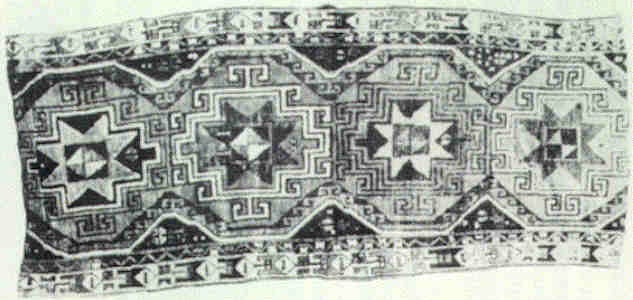

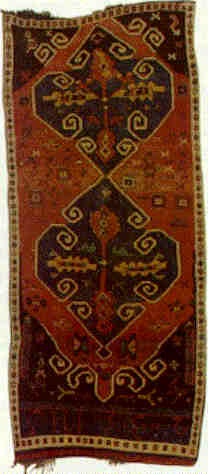

Illustration 3. Hartushi with "Caucasian" turtle,

c. 1930

Technical Analysis

Warp: white, black, brown goat hair, and mohair

Weft: Tan wool, three shoots

Knot: 4x5

Colors: RED, blue, blue-green, purple, orange,

white Size: 104"x49"

Edge: w - 3 blue selvages

Ends: 4" plaits to 1" crossbraid

|

The most persistent and notable field design

is a shield which is referred to as a "turtle" in Kurdish and Turkish. It is

found on about 20% of the Hartushi rugs. This dramatic device is seen in

weavings from the Iranian and (allegedly) Soviet Azerbaijans. It is hard to

believe that it developed from urban influence or was originally conceived to

represent a turtle. It is best known to the rug world from soumack bagfaces

attributed to the Caucasus, one of which appeared on the cover of the 1969

Textile Museum publication, From the Bosphorus to Samarkand, Flat Woven Rugs.

Others recently seen at auctions are not only similar to those found in

Hartushi rugs but are, in fact, identical in at least one case (Illustration 3,

pg. 24), including minor field devices. Perhaps we should reexamine the claimed

Caucasian parentage of the soumak bagfaces, though it is not suggested here that

they are necessarily produced by the Hartushis. For those who favor antique

origins, geometric human figures with arms held out and up can be found on

artifacts from the period 1300 to 800 B.C. attributed to Anatolian peoples,

including Hittites. In addition to the "turtle" (Illustration 3) and a variety

of Memling guls (Illustration 1), eight-pointed stars are common, both as major

field designs and as adornments. In fact, the centers of most "turtles" contain

large, eight-pointed stars.

|

The structures of the Hartushis are quite

uniform. A typical rug would be eight to l2 feet

long and four feet wide with tan or grey wool or

goat hair warps and with wool wefts in natural

or sometimes dyed pile wool. The wool is hard,

strong, and sometimes shiny, lying at an angle

because of the multiple wefts. Although north of

Lake Van the brown sheep influence the color

scheme of the Kars rugs and kilims, the Hakkari

region to the south of the lake has many white

sheep whose wool is available for the pile and

takes the dyes well.

Knots are large and the count is typically

four-by-four or four-by-five per inch. Between

each row of knots there are usually three to

four wefts. The sides usually have thick

selvages either in two bunches with a

figure-eight wrapping or sometimes in flatter,

smaller selvages of three or four bunches. Some

of the selvages have color changes down the

sides. The ends are typically six-inch plaits

connected to a one-inch cross braid and then a

one inch or shorter kilim leading to the pile.

A novel structure in many Hartushi rugs is a

triangular add-on at one or both ends. The

Hartushis share in a large way the Kurdish trait

of turning out rugs in irregular shapes. In the

Hartushis, when the end is pulled tighter at the

sides creating a rounded effect, triangular

wedges are sometimes added from leftover pile

yarn to straighten the end (Illustration 4, pg.

22).

The age of these rugs is not readily

apparent. Few are dated, but the most recent

date we have found is 1973. The earliest,

probably authentic date is 1915 (Illustration

5). A number of the rugs appear to be earlier

than this rug, so we can tentatively conclude

that, while most were woven between 10 and 60

years ago, some were woven in the last century.

As far as we are able to determine,

virtually no Hartushi rugs are now being

produced. Instead, weavers are turning out

smaller lightweight fabrics for the tourist

trade. Then, why are these rugs now on the

market when they were unavailable only a few

years ago?

|

Illustration 4, Hartushi backs, some showing

triangular add-ons

This is a question we put to a number of

people in the Van-Hakkari region during a trip to eastern Turkey in June, 1988.

The most common answer was, "Only recently did the pickers get into the villages

to bring the rugs out," but this is, of course, an incomplete answer. It has

been suggested that political developments in the region might have had an

effect, and indeed some sources claim that rugs have been brought out of

villages in northern Iraq near the Turkish border wherethere have been movements

of people from Iraqi Kurdish villages to resettlement areas. The best

explanation, it seems, is that those who own the rugs no longer prize them as

highly as they do cash or new machine-made rugs which are given in exchange, and

once the process got underway, the profit motive takes the pickers deeper into

the mountains in search of more and more rugs.

It is not at all certain how many Hartushi

rugs will be available for the many collectors who are looking for tribal rugs

untouched by urban or commercial influences. If for several years there is a

glut, this does not mean that they are inexhaustible. Tens of thousands of Jaf

bags flooded the U. S. market in the 1 920s and '30s, but they are now rare

where they originated in Iran and Iraq. There are probably 300 to 500 Hartushi

rugs now in the retail and wholesale outlets of Istanbul, and several hundred

more in the other centers of Turkey. Perhaps a thousand or two still remain to

be brought, out of the mountains. It can be a risky business going into these

villages unless the picker has somehow gained the confidence of the tribesmen

and women. However, greed will win out and, before long, most of the Hartushi

rugs will have been extracted, and many of them will be in Europe and the United

States. During the past few months prices have risen, perhaps indicating that

supplies are drying up -- or that demand is increasing.

It is likely that enough of these rugs will

soon be available to form a group that will find its place in the rug

vocabulary. When this happens, let us begin by discarding the "Herki" label and

calling the rugs after their tribal origin, "Hartushis," or if attribution to

the area rather than the tribe is preferred, "Hakkaris."

|

|

Illustration 5. Dated Hartushi, 1915

Technical Analysis Warp: brown and white goat hair

Weft: Tan wool, two-ply

Knot: 4 1/2x4

Colors: MEDIUM BLUE, red, brown, yellow, white,

blue-green

Size: 110"x47"

Bottom: Short plaits found at the ends in pairs

to 1" crossbraid

Top: s

|