Historical Background

Mustafa Barzani

The Kurdistan Democratic Party of Iraq, the KDP, was formed on 16 August 1946. Before the KDP was formed there was a branch of the Kurdistan Democratic Party of Iran, KDPI, in Suleimaniyeh led by Ibrahim Ahmad. In 1946, the Shurish send Hamza Abdullah to Mahabad to see how they could cooperate with the Iranian Kurds. In Mahabad Hamza met Mulla Mustafa and they discussed the possibility of forming a party on the model of the Kurdistan Democratic Party of Iran. In 1946, the remnants of Hewa, Shurish, Rizgari joined together to form the KDP. When the Kurdish Republic of 1946 was defeated the branch of the KDPI in Suleimaniyeh joined the KDP. On 16 August 1946, a congress was formed in which the formation of the KDP was announced [1]. In this congress the KDP stated the political and economic situation of the Kurds in Iraq were different from that of Iran. It demanded autonomy for the Kurds of Iraq [2]. Mulla Mustafa Barzani was elected as the president of the party and two other landlords, Sheikh Latif and Sheikh Ziad Agha were appointed as vice presidents. Hamza Abdullah was elected its Secretary- General [3].

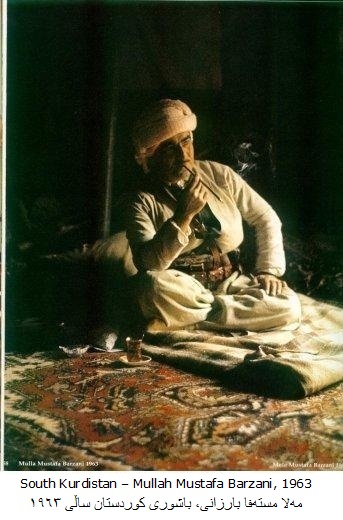

Mulla Mustafa Barzani led a Kurdish revolt in 1943. This revolt and the subsequent events made him one of the greatest Kurdish heroes. He became the symbol of Kurdish resistance for about 32 years. Mulla Mustafa was born in the village of Barzan on 14 March 1903. In 1906, when he still was three years old, he was detained with his mother in Mosul Prison when his brother Abd al-Salaam Barzani led an uprising against the Ottoman Empire [4]. He was of a tribal and religious family. His grandfather, Muhammad, gathered a large following around himself for being a prominent leader of the Naqshbandi order. Mulla Mustafa''s grandfather was famous for his piety. This made his descendants the spiritual leaders of Barzani tribe [5]. Mulla Mustafa was involved in different revolts conducted by his brother Sheikh Ahmad. He led a force of 300 and joined Sheikh Mahmud''s revolt when he was still sixteen years old [6]. In 1932, the British tried to settle the Nestorian Christians who had been expelled by the Turks near Barzan. Sheikh Ahmad, the older brother of Mulla Mustafa, attacked them. The Iraqi forces with the assistance of the British Royal Air Force forced them to retreat to Turkey. They were pardoned and returned to Iraq. They were exiled to Nasiriyeh in Southern Iraq for four years, and then to Suleimaniyeh where he stayed until 1943 [7]. It was in Suleimaniyeh that Mulla Mustafa was in contact with Kurdish intellectuals and nationalists. He was influenced by the idea of Kurdish nationalism in Suleimaniyeh. In 1943, with the help of the Hewa party, Mulla Mustafa escaped from Suleimaniyeh to Barzan where he conducted a revolt against the Iraqi government [8]. So, the first phase of Mulla Mustafa''s revolt began.

Mulla Mustafa''s revolt attained a nationalist character. Apart from his tribesmen, some Kurdish officers and soldiers in the Iraqi army joined Mulla Mustafa. He was able to gather a force of 700 composed of tribesmen and Kurdish army officers and soldiers who deserted the Iraqi army to join him [9]. On 12 February 1945, Mulla Mustafa with the support of Kurdish officers formed a political organisation called the ‘Freedom Group’. The Freedom Group demanded autonomy for the Kurds of Iraq. Its aim was to unite Kurdish tribes and establish contacts with other Kurdish organizations [10].

Mulla Mustafa could not resist the superior forces of Iraq so retreated to Iranian Kurdistan. Mulla Mustafa''s revolt was still in its early stages. He had not yet organised his forces well and had not enough forces to combat the Iraqi army supported by the British Royal Air Force and Kurdish tribes hostile to the Barzani tribe. In September 1945, he retreated to Iranian Kurdistan where there was no government control. His forces formed the backbone of the Kurdish Republic of 1946 in Iran which was announced on 22 January 1946.

After the defeat of the Kurdish Republic of 1946 in Mahabad, Mulla Mustafa had no choice but to seek asylum in the Soviet Union. When the Kurdish Republic was defeated by the Iranian forces in December 1946, Mulla Mustafa tried to reach an agreement with the Shah of Iran over his settlement in Iran, but he did not succeed. His forces were attacked by the Iranian forces and the hostile Kurdish tribes in Iran; he retreated to Iraq. He was caught between three hostile states, Iraq, Iran and Turkey. He finally decided to march towards the Soviet Union in 1947, with 500 of his followers. In this ‘Great March’ Mulla Mustafa with his followers walked about 200 kilometres in 52 days. In their ways to the Soviet Unions they were attacked by the Turkish forces, Iranian forces and the Kurdish tribes of Iran. He finally managed to pass the Araxas River into the Soviet Union on 15 June 1947 where he stayed for about 11 years [11].

The Iraqi “Revolution” of 1958

Abdulkarim Qasim

The Iraqi “Revolution” of

1958, opened a new phase in Kurdish history in Iraq. On 14 July 1958,

‘Free Officers’ in Iraq staged a successful coup against the Hashemite

monarchy which came to be called the “Iraqi Revolution of 1958” [12].

In a power struggle ensued among the free officers, Qasim emerged as the

successful leader of the Iraqi Revolution. Initially Qasim was on good

terms with the Kurds. Article 23 of the Provisional Constitution on 27

July 1958, recognised the Kurds of Iraq as the partners with Arabs in the

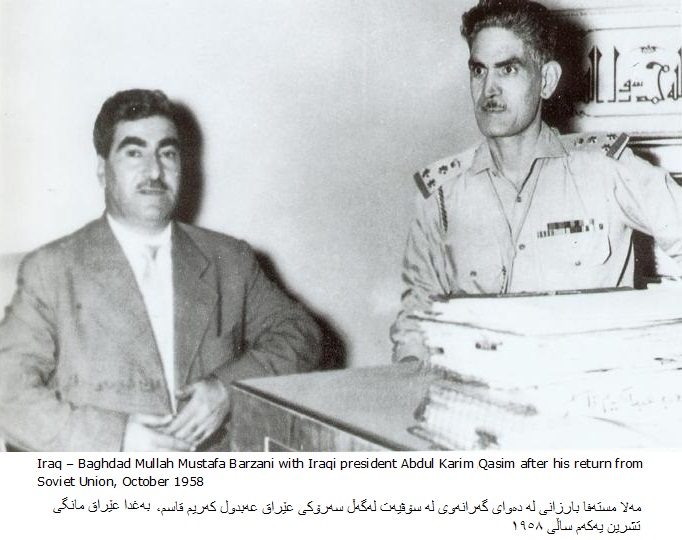

Iraqi state. It guaranteed the Kurdish rights within an Iraqi union. Mulla

Mustafa Barzani who had been living in the Soviet Union for eleven years

was welcomed by Qasim as a national hero on 6 October 1958 [13]. For the

Kurds everything seemed to be desirable.

However, differences soon arose over autonomy and tension grew between

Barzani and Qasim. It seemed that Qasim was not ready to recognise the

rights of the Kurds. In early 1961, the Qasim regime began to harass the

Kurdish leaders; some of them were arrested and Kurdish newspapers were

banned. In July 1961, the KDP was prevented from holding its annual

congress [14]. In July 1961 Mulla Mustafa sent a petition to the

government and demanded autonomy. The demand was rejected by the Iraqi

Revolutionary Council. Mulla Mustafa, who became wary of the intention of

the Qasim’s regime, went to Barzan to prepare for an uprising[15].

Abdulkarim Qasim with Mulla Mustafa

Barzani

War escalated between Mulla Mustafa and the Qasim government in September 1961. When Barzani prepared for the war Qasim refrained from attacking his forces. Instead he agitated the Kurdish tribes hostile to Barzani to fight him. The full-scale fighting began when the Arkon detachment led by Sheikh Abbas Muhammad, a tribe allied to Barzani, angered by the government''s land reform law, attacked a government force between Kirkuk and Suleimaniyeh. The government retaliated by bombarding Barzani villages. Barzani forces retaliated by occupying army’s frontier posts, Kurdish villages and towns. Therefore, a full-scale war began on 11 September 1961. On 16 September the government launched a major offensive which became known as the ‘First Offensive’ [16]. The clashes between the Kurdish forces and the Qasim army continued until he was overthrown in 1963.

War stopped between the government and Kurdish forces when Qasim was

removed from power in a coup led by the Ba''athists and General Abd

al-Salaam Arif. In a power struggle between the Ba''athists and Arif, the

Ba''athist were over-powered by General Arif in November 1963 [17].

Initially, the Iraqi government was not in a position to fight the Kurds.

The Iraqi leaders were more concerned to consolidate their positions

against their rivals. The Kurds too refrained from attacking the weak

government forces hoping that the new government would recognise their

rights. The Arif government ignored Kurdish autonomy, but as a gesture of

good will he appointed two Kurds, Baba Ali Sheikh Mahmud and Brigadier

Fuad Arif, to his cabinet [18].

General Abd al-Salaam Arif soon gave the indication that like his

predecessor Qasim he was not interested in Kurdish autonomy. Tensions soon

grew and clashes began between the government and Kurdish forces. On 10

June 1963, the Iraqi army started its ‘Second Offensive’. The Kurdish

nationalists were labeled as a group of gangs by the government officials.

On 2 July 1963, Lieutenant General Saleh Mahdi Ammash, the Defence

Minister, denied that there was war going on between the Kurds and the

government forces. He considered the fighting in Kurdistan as a national

picnic by the army helped by civilians to destroy the gangs [19]. The

fighting intensified; on 5 April 1965, and on 4 May 1966 the Iraqi army

began their ‘Third and Fourth Offensives’ [20]. During the ‘Fourth

Offensive’ Abd al-Salaam Arif died in a helicopter crash and his brother

General Abd a-Rahman Arif replaced him [21].

General Abd a-Rahman Arif seemed to follow his predecessors'' path. When

Abd al-Salaam Arif was killed Mulla Mustafa announced a one-month

ceasefire. Both the Kurds and the government forces needed a break. Arif

needed to consolidate his position; the Ba''athists had grown strong. He

survived an attempted coup in June 1966. Soon it became evident that Abd

al-Rahman Arif did not want to compromise. He stated he would never grant

autonomy to the Kurds and he would never negotiate with them. The Iraqi

army attacked the Kurdish forces, but suffered a major defeat [22].

Prime Minister Bazzaz, who believed the problem could not be solved by

force, moved in to negotiate with the Kurds. As a result, on 29 June 1966

Prime Minister Bazzaz announced a “Fifteen Point Plan” which was

accepted by Mulla Mustafa. The plan recognised Kurdish national rights

within Iraq. The Kurdish language was recognised as an official language.

The Bazzaz government promised decentralisation of the country''s

political system, free elections of the administrative council and

proportional representation for the Kurds in central government [23]. On 6

August 1966, Bazzaz was forced to resign and his successors had no

intention of implementing his plan. Nevertheless, the Kurds leaned back

and carefully watched the political process in Iraq and maintained

dialogue with Arif. Dissatisfaction among the Kurdish ranks grew, but no

major incident occurred between the government and Kurdish forces.

President Arif was overthrown by a Ba''athist coup led by General Hassan

al-Bakr on 17 July 1968 [24].

The new Ba''ath government was conscious that the Kurdish problem

precipitated the downfall of the previous governments. It tried not to

oppose the Kurds directly, but play them against each other. From the

beginning the Ba''ath government announced its commitment to Bazzaz plan.

Meanwhile it tried to play the Ibrahim Ahmad faction against Mulla Mustafa.

Mulla Mustafa, angry at government attempts to dislodge him, reacted by

opposing the government. He reactivated his clandestine radio and his

forces clashed with the Iraqi army. At the same time there were clashes

between the forces of Ibrahim Ahmad faction and Mulla Mustafa. As the

forces of Ibrahim Ahmad were no match for those of Mulla Mustafa, the

government entered into the fighting in favour of Ibrahim Ahmad faction.

So the full-scale fighting between the government and Mulla Mustafa forces

began in spring 1969. The Ba''athist government launched what became known

as the ‘Fifth Offensive’ [25]. In this fighting Mulla Mustafa''s

forces were able to resist the government attacks well and the Iraqi

government realised it could not make any peace with the Kurds unless

Mulla Mustafa consented.

The Iraqi government finally decided to solve the Kurdish problem by

granting autonomy to the Kurds of Iraq. The Iraqi government''s inability

to defeat the Kurdish forces, fear of intervention by Iran, economic

decline resulting from war, weakness of the army, and instability of the

government forced the Ba''ath regime to find a solution to the Kurdish

problem. After a series of negotiations, on 11 March 1970, the government

signed a peace accord with the Kurds which became known as the

“Manifesto of 11 March 1970”.

The “Manifesto of 11 March 1970” was the most comprehensive autonomy

accord the Kurds had ever had. It was embodied in the new Iraqi

constitution that the Kurds were co-nationals with the Arabs. The Kurds

were given legislative power in their region. One of the two

Vice-Presidents was to be a Kurd. There was a provision for a Kurdistan

development budget, and the Kurdish language was recognised as an official

language beside Arabic [26]. Although Mulla Mustafa was suspicious of the

government sincerity he accept the accord. The Kurds and the government

forces for a while lived in peace.

Lack of mutual trust between Mulla Mustafa and the Iraqi government

prevented the implementation of the “Manifesto of 11 March 1970”. Each

side blamed the other for failing to implement the Manifesto. There were

two major problems in the way, one was oil-rich region of Kirkuk and the

other vice presidency. The Kurds demanded to have a proportion of revenues

from Kirkuk oil and they regarded Kirkuk as an inseparable part of

Kurdistan. The Iraqi government was not ready to relinquish such oil-rich

region. Both sides agreed to conduct a census to determine the future of

the region. The Iraqi government to reduce the number of Kurds settled the

Arabs in the region. The Kurds accused the government of delaying the

census and seeking to arabise Kirkuk, Khanaghin and Sinjar [27]. In July

1970, the KDP nominated Muhammad Habib Karim as a candidate for the Iraqi

vice presidency. His nomination was rejected by the Ba''ath government on

the grounds that his background was Iranian [28].

Further problems arose between Barzani and the Iraqi government. Each side

accused the other of breaching the agreement. The Kurds blamed the

government for building up its armed forces and attacking the autonomous

region. On 7 December 1970, Mulla Mustafa''s son, Idris, escaped an

assassination attempt. On 29 September 1971, and on 15 July 1972, attempts

were made to assassinate Mulla Mustafa Barzani. The Iraqi government was

accused of being involved in these plots [29]. The Ba''ath regime also

accused Barzani of getting arms from Iran, helping the Iranian

Intelligence Service to gather information on Iraqi army, having a new

broadcasting station radio in Iranian soil, siding with the Iranian forces

in certain border clashes, and the training of Kurdish peshmargas (guerrillas)

by the Iranian officers [30]. The tension rose high between the two sides.

However, they tolerated each other until 1974.

The government was not happy with the way the Kurds escalated their

demands so on 11 March 1974, the Iraqi government unilaterally announced

its own “Autonomy Law” for the Kurdish Region [31]. The 1974 Law

limited the Kurdish autonomy and Kurdish region and it was rejected by

Mulla Mustafa Barzani. Fighting between the government and Mulla Mustafa

forces started again. It lasted until March 1975, when Iran and Iraq

signed an agreement in Algiers which ended the Kurdish insurgency.

The Algiers Agreement ended the Kurdish insurgency which had been going on

since 1961. During the OPEC meeting, on 6 March 1975, the Shah of Iran and

Saddam Hussein signed an agreement. In this accord Saddam Hussein agreed

to recognise the Iranian sovereignty over half of the Shat al-Arab,

abandon the Iraqi claim of the Khuzistan province of Iran, and end the

subversion of the Iranian Baluchis along the border with Pakistan. The

Shah undertook to withdraw his support to Kurdish insurgency in Iraq [32].

The Shah immediately withdrew his support and in a few days the Kurdish

revolt came to its abrupt end.

The Algiers agreement had a devastating result for the Kurds. When Barzani

announced the collapse of the armed struggle, thousands of peshmargas

surrendered to the Iraqi forces and about 100,000 to 200,000 peshmargas

and their family and supporters sought asylum in Iran [33]. The Iraqi

government razed to the ground some 800 Kurdish villages along Iraq''s

borders with Iran and Turkey to form a ‘security belt’ to prevent the

contact between the Kurds of Iraq with Turkey and Iran [34]. It was also

taken as a provision to prevent future rebel activity in the area. The

Kurdish families in Iraq were bundled up in army trucks to be settled in

Southern Iraq. They were distributed in groups of five to be settled in

special places build for this purpose or were distributed among the Arab

villages. Life became very difficult for the Kurds who were not accustomed

to the deserts. It is estimated that about 85 percent of those refugees

who returned from Iran under the provision of general amnesty were

deported to those desert camps. There is no exact figure of the Kurds

exiled to Southern Iraq. It is estimated something between 50,000 to

350,000 persons [35]. The casualties of the war were also very high. On 15

January 1979, al-Thawra, an official Iraqi newspaper, put the numbers of

Iraqi army casualties at about 16,000 while the Kurds claimed to have lost

2,000 peshmargas, excluding the civilian casualties who numbered thousands

[36].

Conclusion

The Iraqi “Revolution” of 1958 signified three trends in Kurdish

history in Iraqi Kurdistan. Firstly, for the first time the Kurds of Iraq

were officially recognised as a partner in Iraqi state and their cultural

and political rights were recognised. Before that the Kurds had never

enjoyed an official status. This paved the way for the growth of ‘mass

Kurdish nationalism’ and gave the Kurds a hope that one day they would

be able to enjoy their cultural and political rights.

Secondly, the Iraqi “Revolution” of 1958 signified a new phase in

Kurdish revolt in Iraqi Kurdistan. A revolt which was no more tribal alone

but supported by the different classes in Kurdish society such as teachers,

merchants, students and so on. Thirdly, the Iraqi “Revolution” of 1958

created new lines of division within Kurdish insurgency. This time the

division was not only based on tribal line, but on ideological basis and

differences of opinions that has continued to the existing day.